It must be a shock to hit a floating container at sea. For large vessels it might only cause a scratch, but for powerboats, fishing vessels or sailing vessels it could be fatal. International reports indicate that between 2,000 and 10,000 containers are dropped into the sea each year.

These remain floating for some time in the water or just below the surface.

Why do the containers float, and for how long?

10,000 dropped containers, compared to a total of 5 or 6 mill. transported each year, might seem like a small problem, if the containers were going down immediately – but they are floating.

We can analyse the container as a vessel. A 20´ box has a volume of just over 38 cubic metres, and a 40´ box has a volume of 77 cubic meters. The density of sea water is 1.025, which increases the volumes (or displacement values) to just over 39 and 79 cubic meters respectively.

The force required to push the box under the water, or to sink it, would therefore have to exceed the volume of water to be displaced – 39 tons and 79 tons. It therefore seems that if either size of container is watertight (which is rarely true!), then it will float.

Assuming that containers are rarely watertight, we can estimate that 11 kg of seawater per hour would enter an empty container, taking some 57 days for a 20´ box and 183 days for a 40´ box to sink.

For loaded boxes, we have to look at the nature of packed goods. Today cargo is well secured against damage during handling. Often products are first put into a plastic bag, then stabilized with styropack, or in generic term EPS–material (98 % air), placed in a tight carton and wrapped with plastic on a wooden pallet. The average weight for palletised cargo is 150 to 200 kg pr. cubic metre.

If we look at heavy cargo, like canned tomatoes, they are wrapped with tight plastic in lots of 12 or 24 pcs. The cans are packed side by side, leaving 21% air. Tomatoes have almost the same weight as seawater, and packed tightly into a 20´ box, the weight will be approx 30 ton, plus nearly 3 ton for the box itself, which will still float as you need 39 ton to sink the container.

The average weight for containers is 22 tons, giving an average of 500 kg/m3 for 20´ and 250 kg/m3 for 40´ containers. You need more than 1000 kg/m3 to sink the container. Imagine containers with 10 % EPS–material, they will never sink, as the absorption of water is only 4 % in a year.

In time, the containers at sea will get damaged by waves, from hitting reefs, or due to the increased pressure of water, and sink, but it will take a very long time.

If we estimate that the containers float for an average of three months (very conservative) – this means there would constantly be between 500 and 2,500 containers floating around the world.

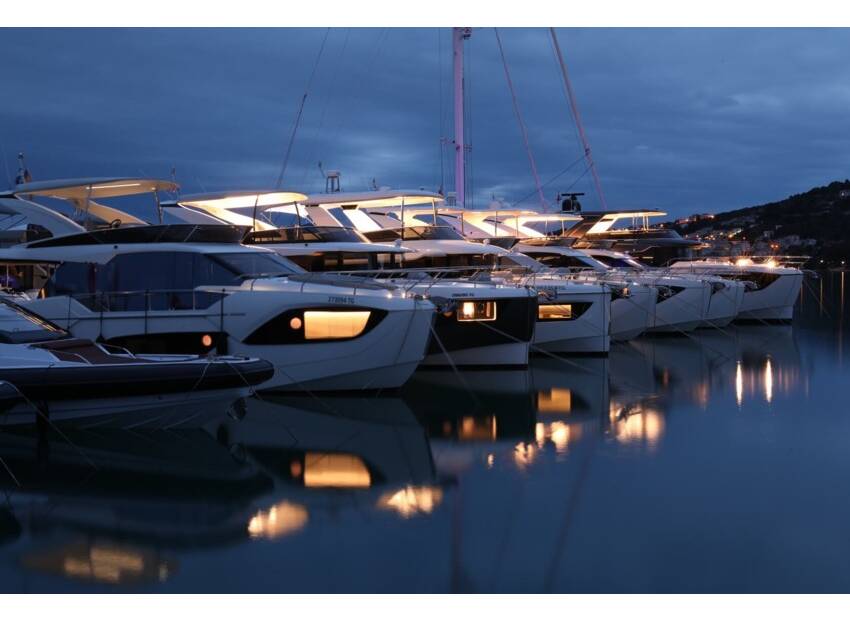

You have a change of seeing these float giants by day, but at night, what can you do? That the danger is not insignificant, confirms the yesterday´s news from the same source about a lone Norwegian sailor who has been rescued from a life raft after his yacht hit a submerged object and sank 48 miles North West of the Isles of Scilly.

There is one solution that might have seemed out landish a few years ago, but not so now. The global thermal imaging giant FLIR is developing a range of thermal cameras for marine use.

FLIR Navigator thermal imagery camera

FLIR’s Tony Kelly says that in a few years thermal cameras, were prohibitvely expensive but are now in the price range for offshore powerboats and cruisers.

‘It’s like GPS was 7 or 8 years ago. GPS 10 years ago was quite specialised, and pretty big and bulky. We’re sure that in a few years time thermal cameras will be just another accessory that you add to your boat. Right now they are are sensible investment for boats who will be spending a lot of time at sea and in unfamiliar places.’

Kelly anticipates that cruising sailors and superyachts will use FLIR thermal c